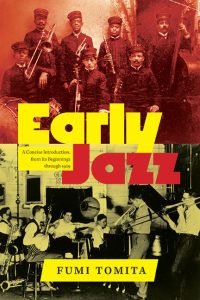

The transition from ragtime to stride . . . from collective improvisation to soloing . . . from the New York Dance Band Sound into the Swing Era. These are some of the subjects covered in depth in Fumi Tomita’s new book, Early Jazz (SUNY Press: 2024).

The book begins in the late 19th Century and traces jazz’s development up until 1929. While giants such as James P. Johnson (photo above), Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, and Louis Armstrong are naturally featured throughout, there are also some interesting segments on lesser known artists such as trumpeter Red Nichols, trombonist Miff Mole, and “the first female jazz trumpet player on record”, Dolly Jones.

My knowledge of Nichols was pretty much limited to his portrayal by Danny Kaye in the 1959 movie, The Five Pennies, which featured a guest appearance by Armstrong. Tomita, Associate Professor of Jazz Pedagogy and Performance at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, described Nichols’ work in the mid-1920s as “among the most progressive white jazz of the era with the merging of improvisation and arranging within a small-group setting.” Nichols recorded with Jimmy Dorsey, Pee Wee Russell, Benny Goodman, and Glenn Miller, among others.

Tomita added that Nichols, “was technically fluid and flexible enough to absorb the nuances of his contemporaries. A great admirer of Bix Beiderbecke, he has been criticized for sounding too much like him, but he was overall a solid player and a good soloist.” Nichols’ main partner in his small groups, Tomita said, was “trombonist Miff Mole, an outstanding pioneer on the trombone who moved away from the New Orleans tailgate tradition to position the instrument as a true solo voice.”

Dolly Jones made her first recording in 1926 with trombonist Al Wynn. Her sound, according to Tomita, “is powerful as she soars above her bandmates who sound frantic by comparison. With modern phrasing and strong command of the instrument, she sadly never got any proper respect or encouragement from the male-dominated jazz world.” Jones spent most of her career in Chicago, playing with pianist Lil Hardin Armstrong, freelancing, and making a cameo appearance in the 1938 movie, Swing!, playing “China Boy” and “I May Be Wrong”. Her mother, Dyer Jones, was also a trumpeter, although she never recorded. However, Dyer Jones taught another female trumpeter, Valaida Snow, who became a star during the Swing Era.

The key figure in the evolution of ragtime into stride was unquestionably James P. Johnson and, according to Tomita, his 1921 Okeh recording of “Carolina Shout” was groundbreaking. “The Okeh version,” he wrote, “is remarkably looser and helped establish stride piano. Fats Waller and Duke Ellington were among those who were inspired enough to slow the roll down to learn the music . . . Johnson establishes the orchestral approach of stride away from ragtime as the right hand plays single-note melodies, sometimes in thirds, chords, and octaves. Freed from strictly providing accompaniment, the left hand has a more prominent role, playing bass notes, chords, melodies, countermelodies, and walking bass lines.”

Ellington and Armstrong were key figures in the movement away from collective improvisation toward more emphasis on soloing. Ellington, Tomita, explained, “crafted his band’s sound around the skills of his valuable sidemen.” Baritone saxophonist Harry Carney “developed a distinctive sound that would support the saxophone section.” Alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges “was perhaps the orchestra’s greatest soloist, renowned for his exquisite ballad playing.”

Armstrong’s Hot Seven recordings, beginning in May 1927, Tomita pointed out, “begin to move away from New Orleans practices towards an emphasis on solo improvisation.” The Chicagoans, a mid-1920s group of white musicians that included clarinetists Frank Teschemacher and Pee Wee Russell, and guitarist Eddie Condon, also began to place “emphasis on individual solos over collective improvisation.”

The beginnings of swing, Tomita wrote, were nurtured in early 1929 when the Ellington band was joined by such soloists as valve trombonist Juan Tizol, trumpeter Cootie Williams, who “together with Carney, Hodges, (clarinetist Barney) Bigard, and (bassist Wellman) Braud would form a powerful nucleus that would carry the Ellington orchestra into the Swing Era.”

Another key moment in the movement toward swing, Tomita wrote, also happened in 1929 when New Orleans bassist George Murphy “Pops” Foster moved to New York to play with pianist Luis Russell’s band. “Mahogany Hall Stomp”, recorded by Russell’s band on March 5, 1929, Tomita said, “features an astonishing performance by Armstrong on three different solos. Building up from a two-feel, the energy from Armstrong’s climactic third solo increases with Foster launching into a swinging walking bass line before Armstrong ends on a long, held triumphant note. It is an astounding performance that hints at the Swing Era.” (By the way, Luis Russell was vocalist Catherine Russell’s father).

Another significant recording, Tomita said, was “One Hour”, recorded by Red McKenzie’s Mound City Blue Blowers and featuring a “landmark solo” by tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. “Hawkins sounds like the future, having mastered a legato or smooth sound that allowed for an expressive and mature performance . . . It was the first entry in Hawkins’ ballad trilogy that would continue with another brilliant solo on 1933’s ‘It’s the Talk of the Town’ by Fletcher Henderson and that would culminate with his classic performance on ‘Body and Soul’ in 1939, a solo that displays his utter mastery of the instrument and an advanced harmonic approach that foreshadowed bebop.”

In the book’s Introduction, Tomita pays homage to Gunther Schuller’s Early Jazz (originally published by Oxford University Press in 1968). It is, Tomita wrote, “one of the most important books ever written about this topic. But it was published over 50 years ago, and an update has been long over overdue.” Tomita’s Early Jazz is relatively short (195 pages) and effectively mixes information about the technical aspects of jazz with some wonderful anecdotes about all the musicians who contributed to its development.”-SANFORD JOSEPHSON