By Sanford Josephson

Lee Konitz was the alto saxophonist in the historic 1949 recording sessions of Miles Davis’ Birth of the Cool, but in 1992, Gerry Mulligan told the Chicago Tribune‘s Howard Reich that, “Miles wanted Sonny Stitt. Gil [Evans] and I both wanted Lee Konitz. His playing with Claude Thornhill’s band sounded so wonderful that we thought he would be the perfect foil opposite Miles . . . Lee had that liquid tone that fit into our concept of the ensemble so well.”

The Thornhill big band was generally considered the forerunner of the Birth of the Cool nonet, which developed when Thornhill band members, Mulligan and Evans, along with other musicians and writers, started experimenting in Evans’ West 55th Street apartment. Konitz joined Thornhill’s band in 1947, and, according to David Adler, writing on the WBGO website the day after Konitz’s death, “he can be heard soloing with striking promise and originality on Gil Evans’ arrangement of ‘Yardbird Suite’ and other Charlie Parker themes.” On Birth of the Cool, Adler added, “His playing on the eerie coda of ‘Moon Dreams’ remains one of that album’s most unconventional moments.” He was the last surviving member of those who participated in the historic recording, which was made in 1949 but not released until 1957 by Capitol Records.

Konitz was born on October 13, 1927, in Chicago. He died April 15, 2020, at the age of 92, in New York from pneumonia, related to COVID-19. When he was 11 years old, Konitz started playing clarinet after hearing Benny Goodman. A year later, he switched to tenor saxophone, but, Adler wrote, “He took up the alto for a gig and discovered that it reflected his true voice . . . Konitz was a great admirer, but never an imitator, of Parker.” He was also influenced by Basie tenor saxophonist Lester Young, as well as Ellington alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges.

As a teenager, Konitz played with and studied under the blind, free jazz pianist Lennie Tristano and maintained an on-and-off musical relationship with him for several years. After the Birth of the Cool experience, he played with trombonist Tyree Glenn and Stan Kenton’s jazz orchestra. According to a profile of Konitz on the concord.com website, “Many purists thought he was ‘selling out’ [playing with Kenton]. However, Konitz said, “It knocked me out that he called me. I’d had a childhood thing from seeing him in theaters. I never cared for the music too much, but it always was an exciting kind of presentation. Also, it meant a steady job.”

As a teenager, Konitz played with and studied under the blind, free jazz pianist Lennie Tristano and maintained an on-and-off musical relationship with him for several years. After the Birth of the Cool experience, he played with trombonist Tyree Glenn and Stan Kenton’s jazz orchestra. According to a profile of Konitz on the concord.com website, “Many purists thought he was ‘selling out’ [playing with Kenton]. However, Konitz said, “It knocked me out that he called me. I’d had a childhood thing from seeing him in theaters. I never cared for the music too much, but it always was an exciting kind of presentation. Also, it meant a steady job.”

Through the years, Konitz worked with a variety of musicians in a variety of settings. In the mid-1970s, he had two steady New York City gigs: Monday and Tuesday nights at Gregory’s in the East ’60s and Wednesday and Thursday nights at Strykers on West 86th St. John S. Wilson of The New York Times caught him at Strykers where he was leading a nonet in December 1976. Pointing out that Konitz was “one of the definitive ‘cool’ saxophonists of the late 1940s,” Wilson singled out “the Gil Evans arrangement of ‘Moon Dreams’, which Mr. Konitz recorded with the Miles Davis nonet almost 30 years ago and an arrangement by Mr. Konitz of ‘Without a Song’ that was a gorgeous melange of strong, tight ensemble playing and exuberant soloing . . . The present group has been together since September and is still feeling its way through some of its material. But when it hits its groove — which is most of the time — the nonet plays with a stimulating flair and polish.”

According to Adler, Konitz, in his later years, “preferred to play standards — and well-worn ones at that, such as ‘Stella By Starlight’ and ‘I’ll Remember April’. In the liner notes to his 1957 Atlantic release, The Real Lee Konitz, he wrote: ‘I feel that in improvisation, the tune should serve as a vehicle for musical variations . . . For this reason, I have never been concerned with finding new tunes to play. I often feel that I could play and record the same tunes over and over and still come up with fresh variations.'”

Konitz’s favorite recording format, Adler said, seemed to be duo albums, made with tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson, guitarist Jim Hall, and pianist Michel Petrucciani, among others. “His two-volume duo outing with Gil Evans, Heroes and Anti-Heroes (French Verve: 1980), Adler wrote, “is worth seeking out for the Mingus interpretations alone.”

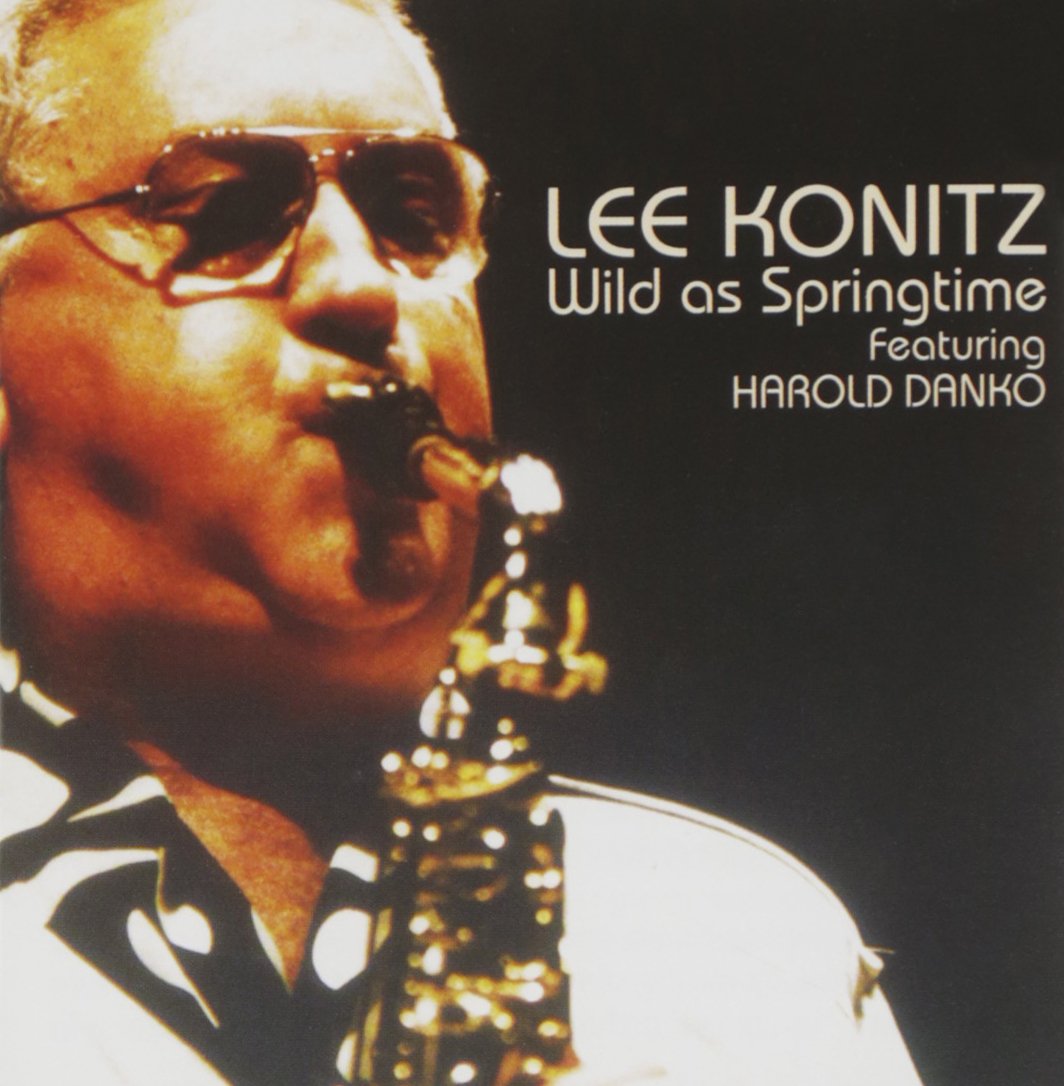

An exceptional duo album, in the opinion of The Guardian‘s John Fordham, was Wild As Springtime (G.F.M. Records: 1984), recorded with pianist Harold Danko. Now Professor Emeritus of Jazz Studies & Contemporary Media at the Eastman School of Music, Danko remembers that album very well. Knowing Konitz’s affinity for playing standards, Danko was delighted that two of his original compositions, “Spring Waltz” and “Silly Samba” were included on the album. “And we co-wrote a piece called ‘Ko’, sort of a play on both of our names (Konitz, Danko). The album also included two Chick Corea tunes, “Hairy Canary” and “Duende”, and Chopin’s “Prelude No. 20”, co-arranged by Konitz and Danko. “He was so great when he was playing original material. I grew up with two older brothers who played saxophone,” Danko continued, “and I kind of looked at Lee as an older brother and certainly as a teacher.” The last time Danko saw Konitz was in 2009 “when we invited him up to Rochester for a concert on his 82nd birthday.”

The late conductor/composer Gunther Schuller, in the liner notes of The Lee Konitz Duets (Milestone: 1968), called Konitz “a rarity — totally dedicated musician, uncompromising and tenacious in the face of adversity, a man who has not lost faith in the original idealism that generated the excitement and ferment of the early bop days and first drew him to jazz.”

On Facebook, baritone saxophonist Kenny Berger recalled having “the honor of being a founding member of his nonet beginning in 1976, and it brought to mind enough stories to fill an entire hard drive, but the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of Lee is how much I learned from him in the three-plus years I worked with him . . .” Drummer Matt Wilson added, also on Facebook: “I was given a gift to share sound with Mr. Konitz for over 25 years in duo, trio, quartet, quintet, nonet, trio with strings, and big band settings. He personified the music being the sound of surprise and embraced vulnerability as an ally. He offered honesty in every note he played . . . “

In 2009, Konitz was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master. Adler recalled that more than 10 years after that, Konitz performed at the induction ceremony, playing Jerome Kern’s “All the Things You Are” and “interspersing his alto saxophone with a scat improvisation, as he had been known to do in recent years.”

Survivors include his sons, Josh and Paul; three daughters, Rebecca, Stephanie, and Karen; three nephews; a great-niece; three grandchildren; and a great-grandchild.