By Sanford Josephson

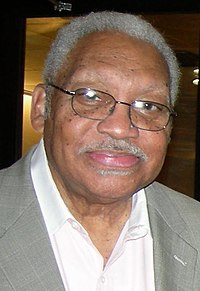

“All I did was make sure they had the best so they could be the best. They did the rest.” That brief statement, in a 1993 Ebony Magazine interview, was pianist/educator Ellis Marsalis’ assessment of his influence on the success of his jazz musician sons — saxophonist Branford, trumpeter Wynton, trombonist Delfeayo, and percussionist Jason. The elder Marsalis was practically a household name in New Orleans for years, but he only became nationally known when his sons, Branford and Wynton, rose to prominence in the 1980s.

“All I did was make sure they had the best so they could be the best. They did the rest.” That brief statement, in a 1993 Ebony Magazine interview, was pianist/educator Ellis Marsalis’ assessment of his influence on the success of his jazz musician sons — saxophonist Branford, trumpeter Wynton, trombonist Delfeayo, and percussionist Jason. The elder Marsalis was practically a household name in New Orleans for years, but he only became nationally known when his sons, Branford and Wynton, rose to prominence in the 1980s.

Marsalis died on Wednesday, April 1, 2020, in New Orleans at the age of 85. The cause, according to Branford, was complications of COVID-19. “My dad, was a giant of a musician and teacher, but an even greater father,” said Branford, in a statement issued after his father death. “He poured everything he had into making us the best of what we could be.”

Wynton, in his blog on wyntonmarsalis.org, called his father “a humble man with a lyrical sound that captured the spirit of place — New Orleans, the Crescent City, the Big Easy, the Curve. He was a stone-cold believer without extravagant tastes. Like many parents, he sacrificed for us and made so much possible. Not only material things, but things of substance and beauty like the ability to hear complicated music and to read books; to see and to contemplate art . . . For me, there is no sorrow, only joy. He went on down the Good Kings Highway, as was his way, a jazz man, ‘with grace and gratitude.'”

Ellis Marsalis was born on November 14, 1934, in New Orleans. He began as a saxophonist before changing to piano in high school. He received a Bachelor’s Degree in Music Education from New Orleans’ Dillard University, later earning a Master’s Degree in Music Education from Loyola University, also in New Orleans. He directed the Jazz Studies program at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts for high school students. Among his students were trumpeter Terence Blanchard and pianist/vocalist Harry Connick, Jr. He later taught at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond and the University of New Orleans where he founded its Jazz Studies program.

While teaching, he continued to work as a musician, often performing with visiting musicians who were playing in New Orleans and, for three years, from 1967-70, touring with New Orleans-based trumpeter Al Hirt. In 1979, he played a gig at New York’s Carnegie Tavern and was praised by John S. Wilson of The New York Times. “Unlike the widely accepted image of jazz musicians from New Orleans,” Wilson wrote, “Mr. Marsalis is not a traditionalist . . . he’s an eclectic performer with a light and graceful touch . . .an exploratory turn of mind.”

A year later, his two older sons, Branford and Wynton, began to rise on the national scene, and their father’s profile rose with them. In 1983, he gave a solo performance at the Carnegie Tavern’s next door neighbor, Carnegie Hall. “Mr. Marsalis’ interpretations were impressive in their economy and steadiness,” wrote The New York Times critic Stephen Holden. “Sticking mainly to the middle register of the keyboard, the pianist offered richly harmonized arrangements in which fancy keyboard work was kept to a minimum, and studious melodic invention, rather than pronounced bass patterns, determined the structures and tempos.”

Marsalis also collaborated on albums with his sons — Standard Time, Vol. 3: The Resolution of Romance (Columbia: 1990) and Joe Cool’s Blues (Columbia: 1995) with Wynton; and Loved Ones (Sony Legacy: 1996) with Brandon.

Joe Cool’s Blues consisted of music composed for the Charlie Brown television specials — some written by the late Vince Guaraldi, and others written by Wynton. Some tracks featured Wynton’s septet, and others featured Ellis’ trio. The album, wrote Billboard‘s Jeff Levenson, “not only showcases the brass man’s compositional talents writing for children, it also features another individual who is clearly responsible for the primacy of the Marsalis name — father Ellis Marsalis.” The elder Marsalis, Levenson pointed out, was a big fan of Guaraldi.

“Guaraldi was almost courageous,” Ellis Marsalis told Levenson, “because he was given a certain kind of freedom, and he went with it. Jazz was never welcome on network television. He took a jam-session approach, which was far more characteristic of jazz musicians than the typical approach taken by Hollywood composers. Those guys might have used jazz techniques within compositional structures, but Guaraldi featured jazz in its most natural form.”

Loved Ones was called “one of the most appealing CDs of the year,” by Los Angeles Times critic Don Heckman. “Give part of the credit,” he wrote, “to the simplicity and the directness of Ellis Marsalis’ concept: an album dedicated to ‘the romantic effect of ladies upon American songwriters via a compilation of such tunes as ‘Laura’, ‘Stella by Starlight’, ‘Sweet Lorraine’, ‘Lulu’s Back in Town’, etc.” Another of the songs on the album was “Dear Dolores”, written by Ellis Marsalis for his wife.

Ellis Marsalis retired from teaching in 2001, continuing to appear regularly at New Orleans’ Snug Harbor jazz club, often accompanied by one or more of his musical sons. In 201l, the National Endowment for the Arts presented its Jazz Masters award to the Marsalis family.

In addition to Branford, Wynton, Delfeayo, and Jason, Ellis Marsalis is survived by his wife, Dolores; two other sons, Ellis Marsalis III and Mboya; a sister; and 13 grandchildren.