By Mitchell Seidel

When you visit the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University in Newark, you’re met with all sorts of jazz ephemera: Lester Young’s saxophone, a green Miles Davis trumpet, a miniature statue of Louis Armstrong, documents from various music luminaries. But one item is a bit more unusual than most—a life-sized cardboard cutout of the late Ed Berger, former Associate Director of the IJS until his retirement in 2011. The cutout, left over from his retirement, remained at the IJS after his death in 2017. It can be said that it’s the only item involving Berger and photography that’s not in an exhibit that opened in November at the Jewish Museum of New Jersey. Berger left a legacy deep in jazz history: record producer, author, editor, scholar and jazz photographer. It is that last talent that is being recognized through January 25 at the JM of NJ.

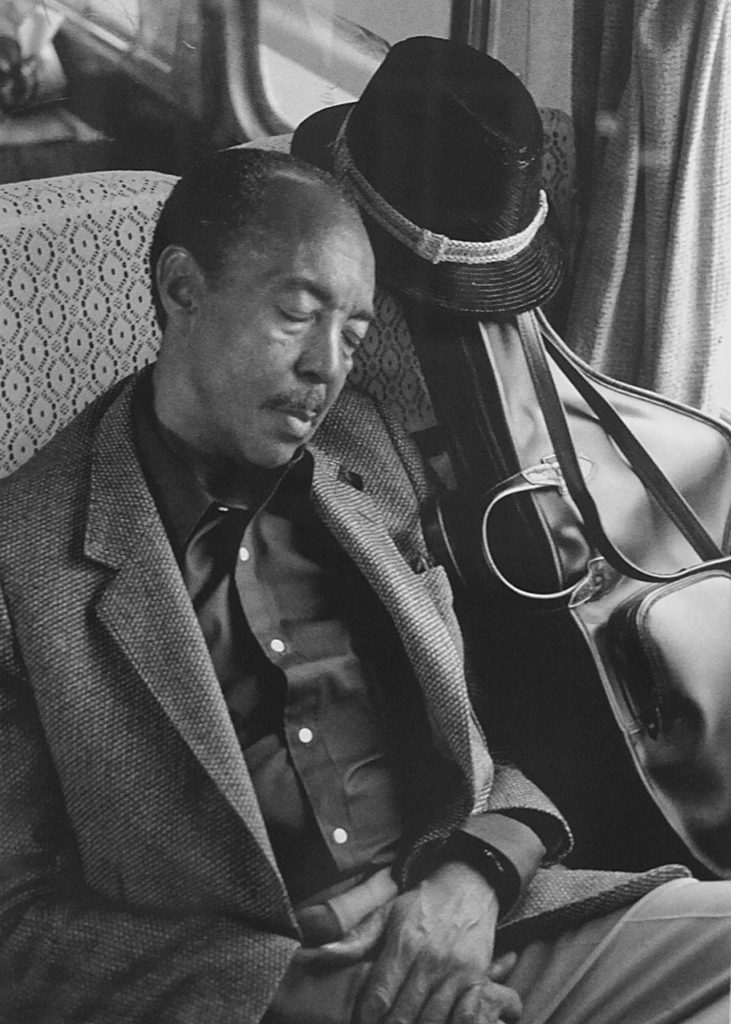

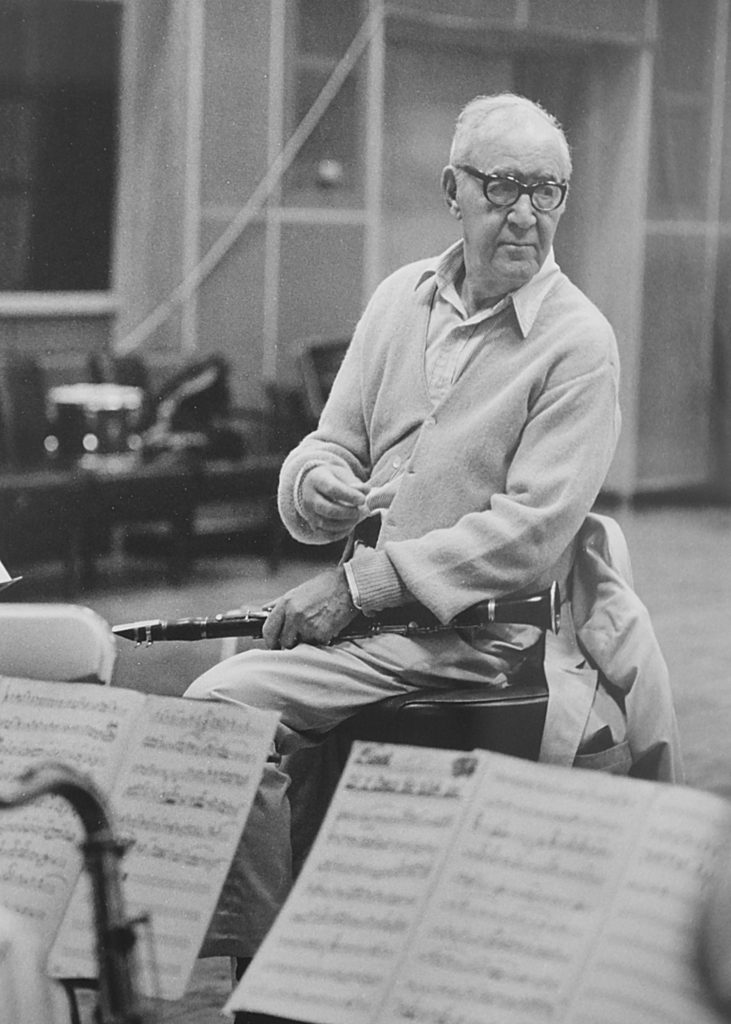

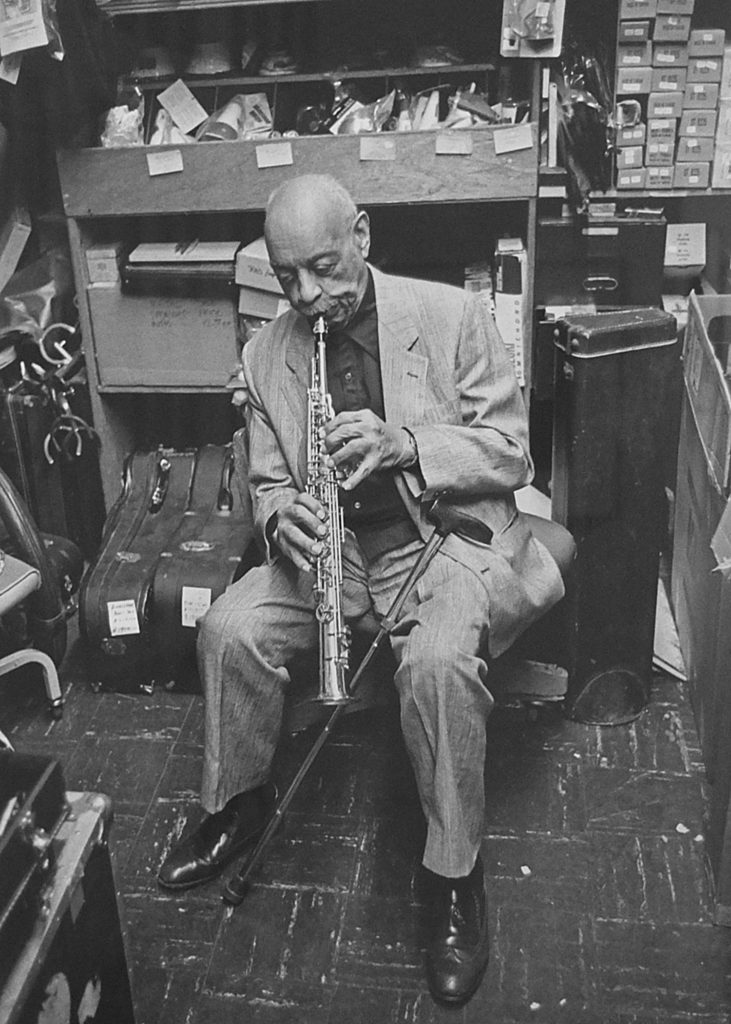

Photos above, top row left to right: Ed Berger with his camera, Harold Land catching some shuteye on a train trip during a tour of Japan, Benny Goodman leading a rehearsal at RCA Records Studio A, Bottom photo: Benny Carter checking out a soprano saxophone in the back room of an LA instrument shop.

Berger had a longtime relationship with Benny Carter, working on his biography with his father, Morroe and James Patrick, serving as his road manager and record producer. It is that work with Carter that forms the backbone of the 30-print exhibit “Ed Berger, The Photographs: A Brief Retrospective,” drawn from a 9,300-image collection of his works at the Oberlin College Conservatory Library and curated by Janice Greenberg and Matthew Gosser.

Because of the nature of Berger’s behind-the-scenes work, his images display jazz musicians in more casual settings: at rehearsals, backstage or in transit on tours. In addition, many of those depicted were shown during activities related to work with the renowned jazz musicians. Unlike most backstage photographers, Berger brought a high degree of technical skill to his work and was as serious about his equipment as he was his subject matter. He started as a hobbyist in his teens, and, as he progressed, often picked photographers’ brains on equipment and techniques. He stuck with film until as late as 2006, eventually switching to digital well after most photographers went to the new technology. A good number of the images from his later years were shot with a Leica rangefinder, and the camera’s high-quality optics are reflected in his images.

Most of the photographs in the show date from the 1980s forward, although one of Louis Armstrong at the Music Circus in Lambertville in 1966 demonstrates the teenaged Berger’s early interest in jazz, fostered by his father. Armstrong is shot onstage from the side, a drum kit partially in view, his arms outstretched, and his typical broad smile in view. It’s unusual because of Berger’s youth and that it was captured during a performance, something he got away from as a more mature photographer.

As Berger became more engaged in the jazz business, so did his access to his subjects. Rather than shooting from the perspective of the audience, as he did as a teenager with Armstrong, the adult Berger was more able to shoot his subjects as if he were a member of the band, which, as a record producer or tour road manager, he actually was.

Trumpeter/cornetist Ruby Braff is depicted in one image alone in a recording studio during a 2002 session. He’s by himself and not playing, more than likely listening to a playback. Braff, not the largest in physical stature, is made to look even smaller in the way the image is framed in Berger’s shot. The background rises large, cathedral-like, behind him, giving the whole activity of being in the recording studio a sense of solitude.

A similar feeling of solitude is presented in a portrait of alto saxophonist Phil Woods at his home in Delaware Water Gap, PA, in April 2005. He is seated, looking up at the photographer, his hands folded around the neck of his horn. The feeling is one of quiet prayer. Woods could be rehearsing or working on a new composition or arrangement. No one else is in evidence. Woods’ only interaction is eye contact with the camera operated by Berger, who, of course is unseen.

Being Carter’s road manager and confidant gave Berger the opportunity to present images with a good deal of intimacy that others may not achieve. One is reminded of the work of the bassist Milt Hinton, whose photographs dating from the 1930s filled two books. While Hinton’s works are rarer, in that he documented an earlier period in jazz history, Berger’s shots are technically superior because of the quality of his gear and more modern technology.

Those who knew Berger as a friend should not be the least bit surprised in the works displayed in Newark: Carter checks out a soprano saxophone in the back room of a Los Angeles instrument shop, saxophonist Harold Land, his hat perched on his instrument case, catching some shuteye on a train trip during a tour of Japan with Carter in 1983, or still another — Benny Goodman— sternly leading a rehearsal at the since-shuttered RCA Records Studio A in midtown Manhattan in 1985.

The Jewish Museum of New Jersey is at historic Congregation Ahavas Sholom, 145 Broadway, Newark, New Jersey 07104. Open Sundays and by appointment (973 698-8489). Free on-site parking. www.jewishmuseum.org