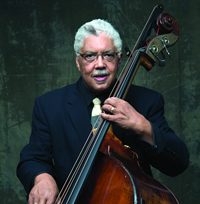

With an incredible resume as a sideman, bandleader, and educator, bassist Rufus Reid represents one of the most significant links to the great jazz tradition. His remarkable accomplishments have not gone unnoticed, and on November 19, Reid will be honored as part of the annual “Giants of Jazz” series at the South Orange Performing Arts Center. This concert, produced for more than 20 years by bassist John Lee, was last held in November 2019, having been canceled in 2020 and 2021 by the pandemic and damage from Hurricane Ida. Those performing and honoring Reid at this year’s event include some of the most celebrated names in jazz, including pianist Bill Charlap, guitarist Russell Malone, and saxophonists Mark Gross, Don Braden, and Eric Alexander, among many others.

Rufus Reid was born on February 10, 1944, in Atlanta; however, most of his youth was spent in Sacramento where he first began as a trumpet player. Reid told me he was exposed to music early on, recalling that, “There was always music in the house. My mother played piano well enough to play hymns in the church, and my father was an amateur pianist who I really didn’t get to know till I was about 18 years old because my parents divorced. I had a sister who sang and played piano. I had two older brothers, who are much older than me. One played tenor sax, and one still plays clarinet very well.” Reid remembered that he first got into jazz when his brother gave him a copy of the Miles Davis album Walkin’ (Prestige: 1959). “I was playing trumpet at the time but had no idea what they were doing on that record; but I knew I loved it.”

Knowing he was likely to get drafted, Reid joined the military after high school, where he played trumpet in the Air Force Band. When serving in the military, he had a lot of down time, and the bass was often not being used, so he began to practice the bass daily. While on a military base in Montgomery, AL, Reid started to play the electric bass in a band and took further notice of the bass players he heard on record, citing Percy Heath and Charles Mingus as early influences. Reid then found further inspiration in the playing of Ray Brown.

“When I was stationed in Japan, I got a chance to see some of the greats like Duke Ellington, Modern Jazz Quartet, Horace Parlan, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Philly Joe Jones, Buddy Rich, Louis Bellson, and Blue Mitchell. I listened to and bought a lot of records. Then I heard Ray Brown live, and I said, ‘That’s it, that’s what I want to do.” He recalled meeting Brown after one of these concerts, a significant event for the then-aspiring bassist. “He and the Oscar Peterson Trio were signing autographs, and Ray Brown saw me. I didn’t look Japanese, and I was taller than most of the people there, and he said, ‘Here, hold my bass.’ After signing autographs, he said, ‘Give me my bass. Who are you?’ I told him I was in the Air Force band, and he said, ‘Come and walk with me to the hotel.’ So, I got the nerve to ask for a lesson. He said, ‘Be at the hotel tomorrow morning at 10. I was there at 9 and ready. I stayed with him for about an hour.” For many years, Reid and Brown remained acquaintances.

After the military, Reid attended Northwestern University in Evanston, IL, a Chicago suburb where he studied music and played in the orchestra. As a young bassist, the Chicago area provided Reid with the connections and experience he needed to become a professional. While in the Windy City, Rufus Reid became the house bassist at the Jazz Showcase. “The Jazz Showcase,” he recalled, “was my school. I got to play with everybody, and most of the guys were much older than me — Dexter Gordon, Gene Ammons, James Moody, Illinois Jacquet, Kenny Dorham, McCoy Tyner, Bobby Hutcherson. Harold Land, Joe Henderson. It was an amazing time for me.” Reid can heard playing at this critical period of development on the album Gene Ammons and Dexter Gordon -The Chase! (Prestige: 1970).

One of the musicians Reid most admired in Chicago was saxophonist Eddie Harris, who was already a well-known recording artist. “I knew some people with Eddie Harris’ phone number, and I just decided to call him. Evidently, he heard me play and knew about me. When we spoke about playing together, he told me to stay in school and get my degree first, and opportunities would come after I graduated. That really messed me up because I was ready to quit school to play with him.” Reid eventually joined Harris after graduation and recorded four albums with him, including Instant Death (Atlantic: 1971) and Is It In (Atlantic: 1974). Harris, Reid said was ‘the most influential person in my entire career.’”

During his time with Harris, Reid was hired by jazz educator Jamey Aebersold to do a bass workshop where he sold about 25 copies of Ray Brown’s Bass Method (Hal Leonard: 1999). He told Harris about selling the books, and Harris recommended that Reid write his own book. He also advised the young bassist to be sure to own the publishing rights to the book. Sound advice that led to the 1974 publication of The Evolving Bassist (Warner Brothers), which still serves as standard repertoire for bass students.

After working for some time with Harris, Reid moved to New York, where he began working with the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Big Band. On the first gig, he was asked to play “Tiptoe,” a difficult chart for bassists. “It was a test,” he recalled. It was with that band that Reid began to gain a reputation in New York. Around that same time, Thad Jones was serving as an Artist-In-Residence at William Paterson University in Wayne, NJ. Through Jones’ connection with the school, Reid met Dr. Martin Krivin and began doing some master classes. When Jones started spending more time in Denmark, he failed to show up to the University, and Krivin was concerned about the program he was building. Krivin called Reid and asked if he knew Thad Jones’ plans or whereabouts. When Reid told him he was unsure of Jones’ plans, Krivin asked Reid if he could help in Jones’ absence. At first, Reid was reluctant because he had come to New York to play and not teach. After some reconsideration, Rufus Reid became Professor Reid, helping to build one of the most celebrated jazz programs in the world. He remained at WPU for more than 20 years and remembers how crazy his schedule was at the time. “I played at Bradley’s in the city a lot during that time, often with Kenny Barron, who also taught at William Paterson. We would teach all day, drag our asses, and fight the traffic to get into the city, and the gig wouldn’t start till 10, and we would play till 2in the morning.” Despite the challenges of juggling teaching and performing, Reid enjoyed his time at the University, is proud of his work there, and appreciated the “support” the faculty and staff gave him. –JAY SWEET

PHOTO BY JIMMY KATZ

A discussion of all the musicians Reid has worked with would be a monumental work, but one of those Reid was connected with for some time was the great trombonist/composer J.J. Johnson. “J.J. was one of my heroes. He was a gentleman and treated the band with the utmost respect. His playing was pristine. The band was Renee Rosnes (piano), Billy Drummond (drums), and Ralph Moore (saxophone), and the group was unbelievable. One time we played in Amsterdam, and J.J. Johnson slipped a note under my hotel door that said, ‘Thanks for last night; you guys played your ass off; love J.J.’ Nobody ever did that! He was a gorgeous man to be around.”

Another of the many notables Reid worked with was tenor saxophonist Stan Getz, a man who was known to be difficult at times. “Playing with Getz was special for me. He used to tell me, ‘You played with Dexter Gordon, and he is a happy drinker, but I am different.’ He wasn’t really a nice guy, but he was okay with me. When he was with me, he didn’t drink. We did a tour with Kenny Barron and Victor Lewis.. We did two recordings together, which we made in one day at the club Jazzhus Montmartre in Paris in 1987 (Anniversary! and Serenity, both on EmArcy: 1991). At the time of the performance, we had a month of playing under our belts. Stan had a golden sound, and we knew we had to play well with him. To me, his worst enemy was when he took the horn out of his mouth, but, musically, he was great. Many Stan Getz nuts believe that the records we made were some of his best, and I have to admit they are wonderful, and I feel blessed to be part of that. At the time of the gig, Stan was really cool.”

In addition to working with legends, Reid has made several albums as a leader and co-leader. “I wanted to be part of a celebrated trio, but it just never clicked. I was not sure I wanted to be a leader, but drummer Akira Tana had a nice musical connection, and we had a band for 10 years (TanaReid) and made six albums.” At 78 years young, Reid is still incredibly active. At the time of our interview, he was preparing for three nights at Dizzy’s Club. Some upcoming projects and releases he is particularly excited about include some recent commissions to further create a genre of composed music with jazz sensibilities. This style of writing can be heard at times on his newest release, Celebration Rufus Reid Trio, with the Sirius Quartet (Sunnyside Records: 2022)

“The future of jazz,” Reid believes, “is in great hands, but there are many more players than opportunities where younger players can hone their skills. I had the support of playing six nights a week for years. Some students I have can play more and show more technique at 19 and 20 than I can ever imagine, but they don’t know what to do with it and haven’t been given the opportunity. I would like the players to be a little more patient and avoid showing off as much. I believe that when I played with Stan Getz, the rhythm section could make him sound better than he could with any other rhythm section; the players of today have so many distractions, but the really creative players will find a way. Some great players are coming out now who are serious and know their history, so that’s encouraging.”

PHOTO BY RONALD STEWART